Tony Abraham Thomas

Continuing Medical Education Unit, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India

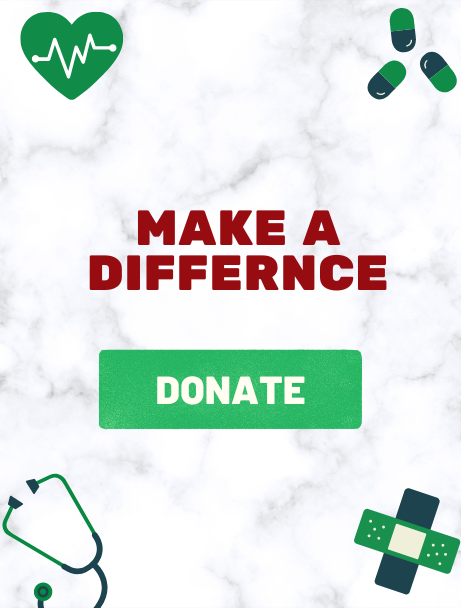

It was a bright sunny morning when a nurse and social worker, accompanied by a group of visiting medical students and a doctor made their way through a village in rural Uttar Pradesh in a spacious four-wheeler. The nurse and the social worker were part of the palliative care team of the Broadwell Christian Hospital, and they were on a mission caring for terminally ill cancer patients in the villages surrounding the hospital. The discomfort of the bumpy ride was adequately compensated by the beauty of the rural landscape with the wide expanses of yellow mustard fields in bloom and the majestic Mahua trees [Figure 1 a and b].

Amidst the laughter and bubbling enthusiasm of the young doctors-in-training, the nurse described their work and the problem of oral cancer in the district. For a village in a developing country, there is a surprisingly large incidence of cancer. Oral cancer is especially prevalent because of the widely prevalent habit of chewing tobacco and smoking. The wounds of oral cancer on the face are significant and very painful sometimes covering a large part of the face, often smelly, disfiguring and inconvenient to take care of. Very few have access to proper medical treatment in the initial stages which meant that cancer grows into advanced stages very often. At that point, there was very little hope for cure.

The four-wheeler gently eased to a stop, and the group made a bee‑line to the first patient whom we were visiting. A toothless smile creased the face of an elderly gentleman sitting on a rope bed when he recognized the nurse and her assistant. It was a meeting of familiar friends.

After the customary greetings, the nurse and the social worker were soon in deep conversation with the elderly man. He had had oral cancer with ulcers in his mouth which were healing with radiation therapy. The conversation was light-hearted and revolved around the elderly man’s present state of health, his current problems, medications, agriculture and farm yield and issues regarding his family. A basin of clean water was then brought in and soon, with dupattas tucked in, the nurse and social worker set themselves to the task of cleaning his eyes and some wounds in his mouth with cotton swabs. The medical students watched in rapt attention, as did a group of children who had materialized out of nowhere and very soon the team had a small audience watching the show. The cleaning and dressing done, the team soon cleaned up and got ready to leave but not before the female of the house gifted a packet of ground pulses into our hands to eat on the way [Figure 2].

There was one more person to visit that morning in another village and conversation crackled as the four-wheeler made its way once again through the picturesque landscape. The

destination was about 30 min away, and after parking the car in the shade of one of the ubiquitous Mahua trees, the group walked to the house of the next patient. This man had cancer, was much more ill than the first and he lay on a cot outside his mud house. A steel plate and tumbler, his last earthly possessions, lay at the feet of the bed in mute testimony to the transitory nature of life. Oral cancer had ravaged his body, creating a large erosive ulcer on his face that made eating difficult. His skeletal emaciated figure lay almost motionless on the bed, but his eyes brightened on seeing the familiar face of the palliative care team. The nurse and her assistant were soon at work, talking to the man, enquiring about his health and family [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3: At the bedside.

Figure 4: Earthly possessions.

As in the first visit, family members, children, and neighbors soon joined in the conversation. A clean basin of water made its way into the gathering and team spent the better part of the next ½ h cleaning the large ulcer on the man’s face, cutting out the slough, removing maggots and flushing the deeper areas with water containing powdered metronidazole. Once the cleaning and dressing were done, the team spent some more time talking with the man, addressing his fears and reassuring him. The family was also educated on wound care and general hygiene. The man was living out his last days, the atmosphere was somber, and the voices were hushed. Yet in the midst of it all, hope and love reigned as the dying man listened with eager ears to the words of his caregivers. It was not often that people spoke to him, sat next to him and touched him and he clearly cherished every moment spent with him. The team closed the interaction with a word of prayer and packed, and the team was soon on their way back to the hospital.

Two lives had been ministered to by the palliative care team, but their work had touched more than just two individuals that day. The families and neighbors in the community, not to mention the young visiting medical students had their liveschanged in some small way by the hours of that morning, by the efforts of a team that ministered to those who would not be cared for otherwise by the medical or social community.

Palliative Care: An interview with Dr. Sunitha Varghese

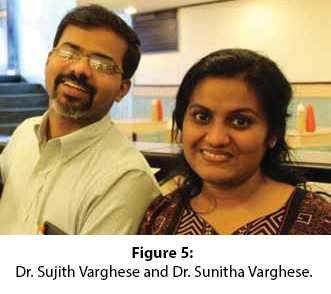

Palliative care in Broadwell Christian Hospital, Fatehpur, Uttar Pradesh started as a small initiative in 2012, spearheaded by Dr. Sunitha Varghese - a community health specialist, trained

Palliative care in Broadwell Christian Hospital, Fatehpur, Uttar Pradesh started as a small initiative in 2012, spearheaded by Dr. Sunitha Varghese - a community health specialist, trained

in Christian Medical College, Vellore who has been working in Fatehpur for almost a decade [Figure 5]. While palliative care is gaining momentum in South India, much of North India remains ignorant to its need. The hospital offers one of the very few home-based care programs in the entire State of Uttar Pradesh - one of India’s largest states. In contrast, Kerala, a much smaller state, has at least 150 palliative care programs-mostly home based. In a candid interview, Dr. Sunitha describes the philosophy behind palliative care and the growth of the palliative care team in Fatehpur.

What is Palliative Care and why is it important?

Some illnesses can be prevented and some can be cured, but there are times when a person cannot be cured despite all efforts. The disease has just progressed to beyond treatment. Can a doctor just send the person away saying, “Sorry, we can’t cure you”? We do not think so. A medical professional cannot just wash his or her hands off the patient once his disease is deemed incurable. We still have a responsibility toward their care. These are individuals who are suffering. They need much care and comfort in the midst of their pain. Individuals with terminal cancer or other terminal illnesses have problems that cannot be addressed in a manner similar to those with curable illnesses. This is where palliative care finds relevance.

Addressing the pain

Physical pain is also complicated, very often requiring Morphine. Morphine is a narcotic that is not easily available. In fact, Broadwell Christian Hospital is the only hospital in the entire district with license for morphine.

While management of physical pain is an important aspect of palliative care, it is only one part of it. There is also a lot of emotional, social, and spiritual pain. The sense of social and emotional isolation and the trauma associated with incurable illnesses is intense. Terminally ill persons are often not involved in daily family activities. They do get left out. Being unable to sit with the family for a meal can be very emotionally painful. In many cases, terminally ill individuals are relegated to a life of solitude in one corner of the house or outside the home, even while their mental faculties are fully functional. There is also the aspect of spiritual pain– many are racked by questions– questions of justice, “Why God does not heal me, do I not have enough faith?” Who will deal with these issues? It requires someone who is trained and equipped to handle these issues. The family members are often not in an emotional state to handle such a situation since they themselves could be reeling with many such questions.

This is what palliative care is all about – training to take care of and support the dying person so that the last days of his/her life are days spent in dignity and reasonable freedom from all sorts of pain. We call it - “putting life into days.”

Palliative care in Broadwell Christian Hospital, Fatehpur

The decision to start palliative care in Fatehpur was taken while I and a small team were caring for my father in the terminal stages of cancer. This is a critical stage since you do not know how long it will last. You just want to do what is best for a dying person for as long as he is alive. Having witnessed the pain that he went through and the difference that our care had made in his life made us realize that this was something worth doing in the village community around us. At the same time, Dr. Ann Thyle who had pioneered palliative care in Lalitpur (Emmanuel Hospital Association [EHA]), had made a presentation of her work which inspired me to take up palliative care in Fatehpur and this was one of the best decisions I have taken in my life. Palliative care fits in very well with EHA’s vision to care for the poor and marginalized.

When we started, we had no idea of the enormity of the need. Within a span of 3 years, we identified over 200 patients within a radius of 20 km from the hospital. We found people in last stages of very advanced cancer. Besides false beliefs in the communities and the myths propagated by quacks, there is no systematic health program to identify and refer persons with such illnesses. Curative care is not easily accessible. The nearest government and private centers for treatment are at least 100 km away and often overloaded. The direct and indirect costs for such treatment are enormous. Without access to timely medical intervention, the disease progresses to an advanced incurable stage.

Home-Based Palliative Care

Our home-based care team consists of a trained palliative care nurse and an assistant (social worker or nurse assistant). They visit patients at their home, understanding that the very ill patient will find it difficult to come to the hospital and wait in the crowded outpatient department for treatment. Visiting at home also gives ample time to observe the surroundings, assess social and economic situations and do a bit of health teaching. The team members address medical symptoms and give appropriate medication, dress their wounds and teach the family how to best care for the patient. The frequency of the home visit is determined by how ill the patient is. Those who are not very sick are visited less often (once a month), while those who are sick are visited more frequently (once a week or even every day). Toward the end of a person’s life, his needs are more and he requires more intense care. The nurse in the field communicates with me by mobile to consult about medications. I make a home visit if the nurse is not able to make sense of the presenting symptoms and signs. The team in the field reports back to me about the condition of the patients at the end of each visit and I help them plan for the next goal in care for those patients.

Our home-based care team consists of a trained palliative care nurse and an assistant (social worker or nurse assistant). They visit patients at their home, understanding that the very ill patient will find it difficult to come to the hospital and wait in the crowded outpatient department for treatment. Visiting at home also gives ample time to observe the surroundings, assess social and economic situations and do a bit of health teaching. The team members address medical symptoms and give appropriate medication, dress their wounds and teach the family how to best care for the patient. The frequency of the home visit is determined by how ill the patient is. Those who are not very sick are visited less often (once a month), while those who are sick are visited more frequently (once a week or even every day). Toward the end of a person’s life, his needs are more and he requires more intense care. The nurse in the field communicates with me by mobile to consult about medications. I make a home visit if the nurse is not able to make sense of the presenting symptoms and signs. The team in the field reports back to me about the condition of the patients at the end of each visit and I help them plan for the next goal in care for those patients.

Terminally, ill patients have many emotional needs. They struggle with fear, guilt, anger toward family members, and unresolved conflicts. As we talk to the patients and their families, we try to clarify issues and resolve them as far as is possible. We have witnessed a lot of healing within families and within the individuals. Many confess the sins of their past, their guilt and sorrows and find spiritual healing in their confession. Dealing with this emotional and spiritual pain is a huge aspect of our care as palliative care workers.

Besides addressing the pain of being isolated by their family, we try to ease the pain of social rejection by the community. Toward this, we hold community meetings, creating awareness, and dispelling myths. The aim is to develop a community that is compassionate toward those who are dying. Sometimes it is as simple as just telling the villagers that cancer is not contagious, that it is safe to visit and talk to a cancer patient and listen to their wise words [Figure 6]. We encourage the family and village community to eat together with them. Eating together is a major social event and brings about a lot of healing.

Ultimately, we are trying to help say goodbye to the patient in an atmosphere of cheerfulness, family, and freedom from pain. Life is precious and priceless. As medical professionals, we take a lot of efforts at the beginning of life, to ensure that all goes well. It is also important to ensure that all goes well at the end of life.

What changes have you seen in families?

There have been tremendous changes we have witnessed among families that we have been involved with. Simply dispelling their fears about cancer and helping them empathize with the feelings of the ill person leads to significant changes in perception. There have been several people from different families who have come back to us after the death of a patient, recounting how much they felt supported and helped by the work of the team. They were also peaceful about seeing their beloved one depart without pain. They felt prepared to say goodbye. They are grateful for our interaction and for all the good memories we helped create in the last days of a dying family member. This is a great encouragement for us.

We also take the opportunity to educate the community about cancer, prevention, and treatment. In addition, we talk about dignity in death. In every village that we visit, much time is given to spread awareness about these issues.

Plans for the future

We are in the process of organizing a cancer action group in the district comprised individuals who have lost a loved one to cancer. It is envisioned that this action group will lobby for the right to health care and timely screening and cure for cancer in the district so that the future for persons with cancer in our district will no longer be so bleak. We are also working with our dental department to do a systematic screening and early identification of oral cancer in our population. Over the period of 3 years, we have seen more than 200 patients and have maintained records carefully. We hope to be able to study this data in the future to improve our care. There is much need for palliative care in Rural India. I believe that this is an important way in which we can create compassionate communities in our country, transforming communities through caring.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.